he James Webb Space Telescope has been a long time coming. When it launches later this year, the observatory will be the largest and most complex telescope ever sent into orbit. Scientists have been drafting and redrafting their dreams and plans for this unique tool since 1989.

The mission was originally scheduled to launch between 2007 and 2011, but a series of budget and technical issues pushed its start date back more than a decade. Remarkably, the core design of the telescope hasn’t changed much. But the science that it can dig into has. In the years of waiting for Webb to be ready, big scientific questions have emerged. When Webb was an early glimmer in astronomers’ eyes, cosmological revolutions like the discoveries of dark energy and planets orbiting stars outside our solar system hadn’t yet happened.

“It’s been over 25 years,” says cosmologist Wendy Freedman of the University of Chicago. “But I think it was really worth the wait.”

An audacious plan

Webb has a distinctive design. Most space telescopes house a single lens or mirror within a tube that blocks sunlight from swamping the dim lights of the cosmos. But Webb’s massive 6.5-meter-wide mirror and its scientific instruments are exposed to the vacuum of space. A multilayered shield the size of a tennis court will block light from the sun, Earth and moon.

For the awkward shape to fit on a rocket, Webb will launch folded up, then unfurl itself in space (see below, What could go wrong?).

“They call this the origami satellite,” says astronomer Scott Friedman of the Space Telescope Science Institute, or STScI, in Baltimore. Friedman is in charge of Webb’s postlaunch choreography. “Webb is different from any other telescope that’s flown.”

Its basic design hasn’t changed in more than 25 years. The telescope was first proposed in September 1989 at a workshop held at STScI, which also runs the Hubble Space Telescope.

At the time, Hubble was less than a year from launching, and was expected to function for only 15 years. Thirty-one years after its launch, the telescope is still going strong, despite a series of computer glitches and gyroscope failures (SN Online: 10/10/18).

The institute director at the time, Riccardo Giacconi, was concerned that the next major mission would take longer than 15 years to get off the ground. So he and others proposed that NASA investigate a possible successor to Hubble: a space telescope with a 10-meter-wide primary mirror that was sensitive to light in infrared wavelengths to complement Hubble’s range of ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared.

Infrared light has a longer wavelength than light that is visible to human eyes. But it’s perfect for a telescope to look back in time. Because light travels at a fixed speed, looking at distant objects in the universe means seeing them as they looked in the past. The universe is expanding, so that light is stretched before it reaches our telescopes. For the most distant objects in the universe — the first galaxies to clump together, or the first stars to burn in those galaxies — light that was originally emitted in shorter wavelengths is stretched all the way to the infrared.

Giacconi and his collaborators dreamed of a telescope that would detect that stretched light from the earliest galaxies. When Hubble started sharing its views of the early universe, the dream solidified into a science plan. The galaxies Hubble saw at great distances “looked different from what people were expecting,” says astronomer Massimo Stiavelli, a leader of the James Webb Space Telescope project who has been at STScI since 1995. “People started thinking that there is interesting science here.”

In 1995, STScI and NASA commissioned a report to design Hubble’s successor. The report, led by astronomer Alan Dressler of the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, Calif., suggested an infrared space observatory with a 4-meter-wide mirror.

The bigger a telescope’s mirror, the more light it can collect, and the farther it can see. Four meters wasn’t that much larger than Hubble’s 2.4-meter-wide mirror, but anything bigger would be difficult to launch.

Dressler briefed then-NASA Administrator Dan Goldin in late 1995. In January 1996 at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting, Goldin challenged the scientists to be more ambitious. He called out Dressler by name, saying, “Why do you ask for such a modest thing? Why not go after six or seven meters?” (Still nowhere near Giacconi’s pie-in-the-sky 10-meter wish.) The speech received a standing ovation.

Six meters was a larger mirror than had ever flown in space, and larger than would fit in available launch vehicles. Scientists would have to design a telescope mirror that could fold, then deploy once it reached space.

The telescope would also need to cool itself passively by radiating heat into space. It needed a sun shield — a big one. The origami telescope was born. It was dubbed James Webb in 2002 for NASA’s administrator from 1961 to 1968, who fought to support research to boost understanding of the universe in the increasingly human-focused space program. (In response to a May petition to change the name, NASA investigated allegations that James Webb persecuted gay and lesbian people during his government career. The agency announced on September 27 that it found no evidence warranting a name change.)

Goldin’s motto at NASA was “Faster, better, cheaper.” Bigger was better for Webb, but it sure wasn’t faster — or cheaper. By late 2010, the project was more than $1.4 billion over its $5.1 billion budget (SN: 4/9/11, p. 22). And it was going to take another five years to be ready. Today, the cost is estimated at almost $10 billion.

The telescope survived a near-cancellation by Congress, and its timeline was reset for an October 2018 launch. But in 2017, the launch was pushed to June 2019. Two more delays in 2018 pushed the takeoff to May 2020, then to March 2021. Some of those delays were because assembling and testing the spacecraft took longer than NASA expected.

Other slowdowns were because of human errors, like using the wrong cleaning solvent, which damaged valves in the propulsion system. Recent shutdowns due to the coronavirus pandemic pushed the launch back a few more months.

“I don’t think we ever imagined it would be this long,” says University of Chicago’s Freedman, who worked on the Dressler report. But there’s one silver lining: Science marched on.

The age conflict

The first science goal listed in the Dressler report was “the detailed study of the birth and evolution of normal galaxies such as the Milky Way.” That is still the dream, partly because it’s such an ambitious goal, Stiavelli says.

“We wanted a science rationale that would resist the test of time,” he says. “We didn’t want to build a mission that would do something that gets done in some other way before you’re done.”

Webb will peek at galaxies and stars as they were just 400 million years after the Big Bang, which astronomers think is the epoch when the first tiny galaxies began making the universe transparent to light by stripping electrons from cosmic hydrogen.

But in the 1990s, astronomers had a problem: There didn’t seem to be enough time in the universe to make galaxies much earlier than the ones astronomers had already seen. The standard cosmology at the time suggested the universe was 8 billion or 9 billion years old, but there were stars in the Milky Way that seemed to be about 14 billion years old.

“There was this age conflict that reared its head,” Freedman says. “You can’t have a universe that’s younger than the oldest stars. The way people put it was, ‘You can’t be older than your grandmother!’”

In 1998, two teams of cosmologists showed that the universe is expanding at an ever-increasing rate. A mysterious substance dubbed dark energy may be pushing the universe to expand faster and faster. That accelerated expansion means the universe is older than astronomers previously thought — the current estimate is about 13.8 billion years old.

“That resolved the age conflict,” Freedman says. “The discovery of dark energy changed everything.” And it expanded Webb’s to-do list.

Dark energy

Top of the list is getting to the bottom of a mismatch in cosmic measurements. Since at least 2014, different methods for measuring the universe’s rate of expansion — called the Hubble constant — have been giving different answers. Freedman calls the issue “the most important problem in cosmology today.”

The question, Freedman says, is whether the mismatch is real. A real mismatch could indicate something profound about the nature of dark energy and the history of the universe. But the discrepancy could just be due to measurement errors.

Webb can help settle the debate. One common way to determine the Hubble constant is by measuring the distances and speeds of far-off galaxies. Measuring cosmic distances is difficult, but astronomers can estimate them using objects of known brightness, called standard candles. If you know the object’s actual brightness, you can calculate its distance based on how bright it seems from Earth.

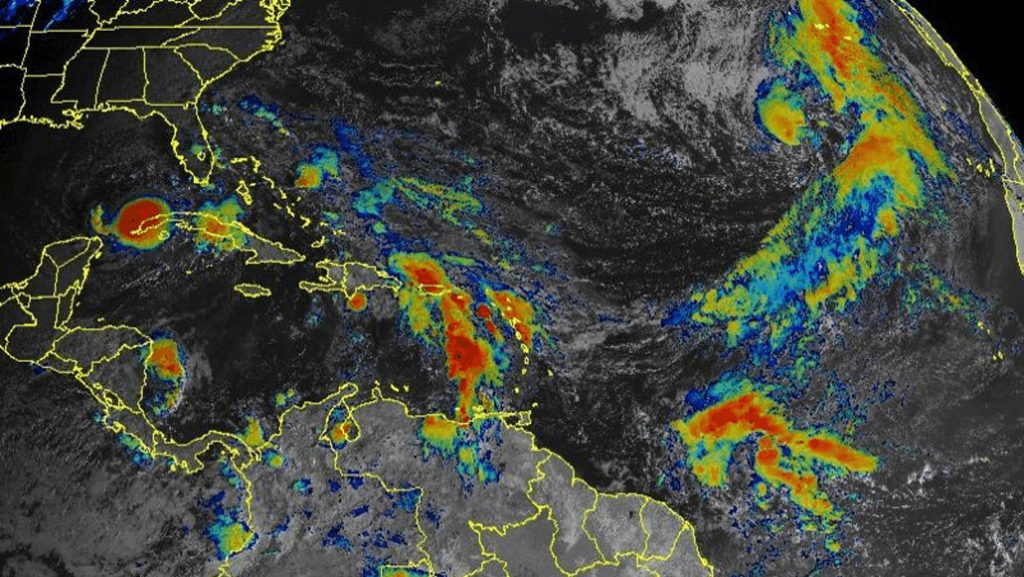

Studies using supernovas and variable stars called Cepheids as candles have found an expansion rate of 74.0 kilometers per second for approximately every 3 million light-years, or megaparsec, of distance between objects. But using red giant stars, Freedman and colleagues have gotten a smaller answer: 69.8 km/s/Mpc.

Other studies have measured the Hubble constant by looking at the dim glow of light emitted just 380,000 years after the Big Bang, called the cosmic microwave background. Calculations based on that glow give a smaller rate still: 67.4 km/s/Mpc. Although these numbers may seem close, the fact that they disagree at all could alter our understanding of the contents of the universe and how it evolves over time. The discrepancy has been called a crisis in cosmology (SN: 9/14/19, p. 22).

In its first year, Webb will observe some of the same galaxies used in the supernova studies, using three different objects as candles: Cepheids, red giants and peculiar stars called carbon stars.

The telescope will also try to measure the Hubble constant using a distant gravitationally lensed galaxy. Comparing those measurements with each other and with similar ones from Hubble will show if earlier measurements were just wrong, or if the tension between measurements is real, Freedman says.

Without these new observations, “we were just going to argue about the same things forever,” she says. “We just need better data. And [Webb] is poised to deliver it.”

Exoplanets

Perhaps the biggest change for Webb science has been the rise of the field of exoplanet explorations.

“When this was proposed, exoplanets were scarcely a thing,” says STScI’s Friedman. “And now, of course, it’s one of the hottest topics in all of science, especially all of astronomy.”

The Dressler report’s second major goal for Hubble’s successor was “the detection of Earthlike planets around other stars and the search for evidence of life on them.” But back in 1995, only a handful of planets orbiting other sunlike stars were even known, and all of them were scorching-hot gas giants — nothing like Earth at all.

Since then, astronomers have discovered thousands of exoplanets orbiting distant stars. Scientists now estimate that, on average, there is at least one planet for every star we see in the sky. And some of the planets are small and rocky, with the right temperatures to support liquid water, and maybe life.

Most of the known planets were discovered as they crossed, or transited, in front of their parent stars, blocking a little bit of the parent star’s light. Astronomers soon realized that, if those planets have atmospheres, a sensitive telescope could effectively sniff the air by examining the starlight that filters through the atmosphere.

The infrared Spitzer Space Telescope, which launched in 2003, and Hubble have started this work. But Spitzer ran out of coolant in 2009, keeping it too warm to measure important molecules in exoplanet atmospheres. And Hubble is not sensitive to some of the most interesting wavelengths of light — the ones that could reveal alien life-forms.

That’s where Webb is going to shine. If Hubble is peeking through a crack in a door, Webb will throw the door wide open, says exoplanet scientist Nikole Lewis of Cornell University. Crucially, Webb, unlike Hubble, will be particularly sensitive to several carbon-bearing molecules in exoplanet atmospheres that might be signs of life.

“Hubble can’t tell us anything really about carbon, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane,” she says.

If Webb had launched in 2007, it could have missed this whole field. Even though the first transiting exoplanet was discovered in 1999, their numbers were low for the next decade.

Lewis remembers thinking, when she started grad school in 2007, that she could make a computer model of all the transiting exoplanets. “Because there were literally only 25,” she says.

Between 2009 and 2018, NASA’s Kepler space telescope raked in transiting planets by the thousands. But those planets were too dim and distant for Webb to probe their atmospheres.

So the down-to-the-wire delays of the last few years have actually been good for exoplanet research, Lewis says. “The launch delays were one of the best things that’s happened for exoplanet science with Webb,” she says. “Full stop.”

That’s mainly thanks to NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, which launched in April 2018. TESS’ job is to find planets orbiting the brightest, nearest stars, which will give Webb the best shot at detecting interesting molecules in planetary atmospheres.

If it had launched in 2018, Webb would have had to wait a few years for TESS to pick out the best targets. Now, it can get started on those worlds right away. Webb’s first year of observations will include probing several known exoplanets that have been hailed as possible places to find life. Scientists will survey planets orbiting small, cool stars called M dwarfs to make sure such planets even have atmospheres, a question that has been hotly debated.

If a sign of life does show up on any of these planets, that result will be fiercely debated, too, Lewis says. “There will be a huge kerfuffle in the literature when that comes up.” It will be hard to compare planets orbiting M dwarfs with Earth, because these planets and their stars are so different from ours. Still, “let’s look and see what we find,” she says.

A limited lifetime

With its components assembled, tested and folded at Northrop Grumman’s facilities in California, Webb is on its way by boat through the Panama Canal, ready to launch in an Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana. The most recent launch date is set for December 18.

For the scientists who have been working on Webb for decades, this is a nostalgic moment.

“You start to relate to the folks who built the pyramids,” Stiavelli says.

Other scientists, who grew up in a world where Webb was always on the horizon, are already thinking about the next big thing.

“I’m pretty sure, barring epic disaster, that [Webb] will carry my career through the next decade,” Lewis says. “But I have to think about what I’ll do in the next decade” after that.

Unlike Hubble, which has lasted decades thanks to fixes by astronauts and upgrade missions, Webb has a strictly limited lifetime. Orbiting the sun at a gravitationally fixed point called L2, Webb will be too far from Earth to repair, and will need to burn small amounts of fuel to stay in position. The fuel will last for at least five years, and hopefully as much as 10. But when the fuel runs out, Webb is finished. The telescope operators will move it into retirement in an out-of-the-way orbit around the sun, and bid it farewell.