Ancient reptiles saw red before turning red

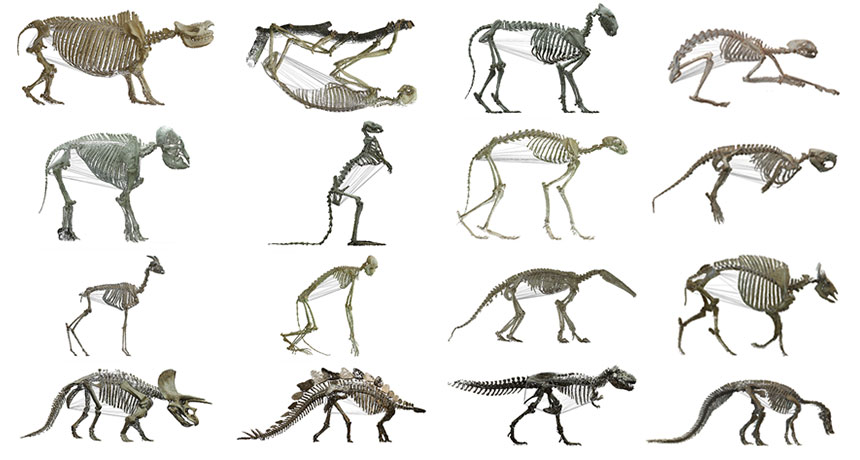

You’ve got to see it to be it. A heightened sense of red color vision arose in ancient reptiles before bright red skin, scales and feathers, a new study suggests. The finding bolsters evidence that dinosaurs probably saw red and perhaps displayed red color.

The new finding, published in the Aug. 17 Proceedings of the Royal Society B, rests on the discovery that birds and turtles share a gene used both for red vision and red coloration. More bird and turtle species use the gene, called CYP2J19, for vision than for coloration, however, suggesting that its first job was in sight.

“We have this single gene that has two very different functions,” says evolutionary biologist Nicholas Mundy of the University of Cambridge. Mundy’s team wondered which function came first: the red vision or the ornamentation.

In evolution, what an animal can see is often linked with what others can display, says paleontologist Martin Sander of the University of Bonn in Germany, who did not work on the new study. “We’re always getting at color from these two sides,” he says, because the point of seeing a strong color is often reading visual signals.

Scientists already knew that birds use CYP2J19 for vision and color. In bird eyes, the gene contains instructions for making bright red oil droplets that filter red light. Other forms of red color vision evolved earlier in other animals, but this form allows birds to see more shades of red than humans can. Elsewhere in the body, the same gene can code for pigments that stain feathers red. Turtles are the only other land vertebrates with bright red oil droplets in their eyes. But scientists weren’t sure if the same gene was responsible, Mundy says.

His team searched for CYP2J19 in the DNA of three turtle species: the western painted turtle, Chinese soft-shell turtle and green sea turtle. All three have the gene. Both birds and turtles, the researchers conclude, inherited the gene from a shared ancestor that lived at least 250 million years ago. (Crocodiles and alligators, close relatives of birds and turtles, probably lost the gene sometime after splitting from this common ancestor, Mundy says.)

Next, the scientists turned their attention to the gene’s function. Mundy’s team studied western painted turtles, which have a striking red shell. As in red birds, CYP2J19 is active in the eyes and bodies of these turtles, the scientists found, suggesting that the gene is involved in both vision and coloration.

Because most birds and turtles can see red, but only some have red feathers or scales, the researchers think the great-granddaddy of modern turtles and birds probably used the gene for vision, too. Whether that common ancestor was colored red is unclear.

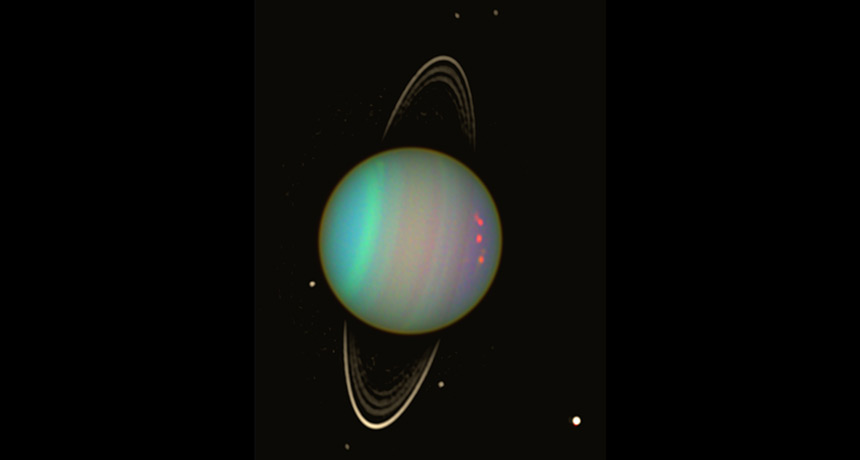

That very old reptile would have passed CYP2J19 down to its descendants, including dinosaurs. Mounting evidence has pointed to dinosaurs as colorful, with good color vision. But the specifics of their coloration have been elusive. This study points to red as one color they could probably see, and perhaps display.

“If you would have asked me 10 years ago, ‘Will we ever know the color of dinosaurs?’” Sander says, “I would have said, ‘No way!’” But studies like this one are a new lens into dinosaur color. Seeing can mean displaying, and this study is solid evidence that dinosaurs saw red, Sander says. In the past, “we couldn’t really say that.”