When mouth microbes pal up, infection ensues

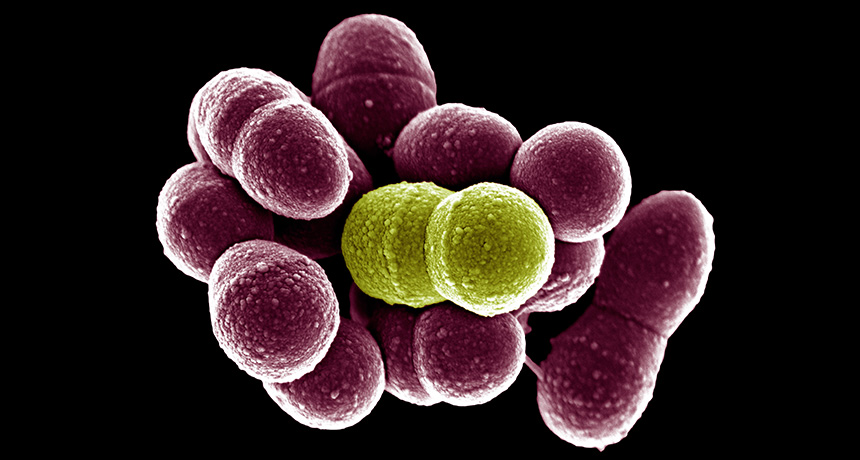

Normally harmless mouth bacteria can be a bad influence. When they pal around with tooth- and gum-attacking microbes, they can help those pathogens kick into high gear. This teamwork lets infections spread more easily — but also could offer a target for new treatments, scientists report online June 28 in mBio.

The way that bacteria interact with each other to cause disease is still poorly understood, says study coauthor Apollo Stacy, of the University of Texas at Austin. Lab work often focuses on individual bacteria species, but managing the communities of microbes found in living organisms is a more complex task. The new finding suggests that bacteria can change their metabolism in response to the presence or absence of other bacteria. A benign species of bacteria excretes oxygen, allowing the second species to switch to a more efficient aerobic means of energy production and helping it become a more robust pathogen.

This is the first time a normally harmless mouth bacterium has been shown to change a pathogen’s metabolism to make the microbe more dangerous, says Vanessa Sperandio, a microbiologist at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas who wasn’t part of the study. Similar interactions have been shown between gut bacteria, she says, but “it’s a very new field of research and there are very few examples.”

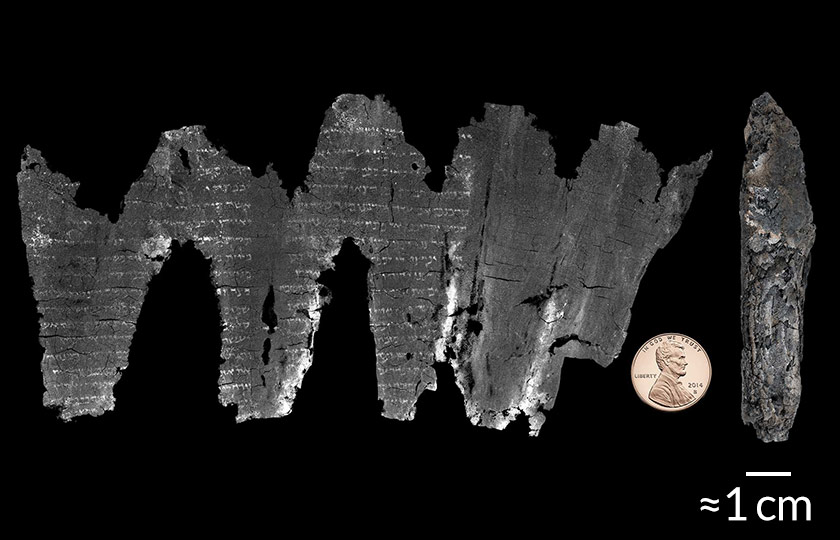

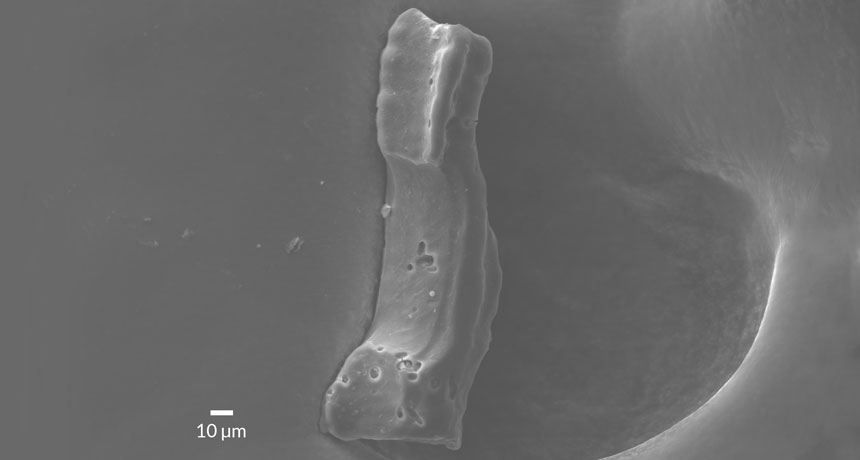

Stacy and his collaborators examined the relationship between two species of bacteria that tend to grow in the same place in the mouth. One, Streptococcus gordonii, is found in healthy mouths and only occasionally causes disease. The other, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, frequently causes aggressive tooth and gum infections.

The researchers knew from previous work that the pathogenic bacteria grew better with a coconspirator. To figure out why, Stacy says, “we asked, ‘What genes do they need to live when they’re by themselves?’” The team compared the solo-living genes to those active in the pathogen while growing alongside S. gordonii. The analysis revealed that the pathogenic bacteria switched their metabolism when S. gordonii was around.

When A. actinomycetemcomitans grew alone, they produced energy without using oxygen — a slow way to grow. But with S. gordonii nearby, the pathogenic bacteria took advantage of the oxygen released by their neighbors and increased their energy production. When tested in mice, that increased energy let the pathogen grow faster and survive better in a wound.

The findings are part of a growing body of research showing that bacteria can sense the presence of other bacteria and adjust their behavior accordingly.

“This system has allowed us to begin to understand that microbes are really astute at evaluating this biochemistry, and in response, they have very specific behaviors,” says Marvin Whiteley, a microbiologist at the University of Texas at Austin who worked with Stacy.

Stacy plans to test the phenomenon in other bacteria pairs to see whether it holds up beyond these two species. Understanding the way bacteria interact with each other could let doctors target infections more efficiently, he says. For instance, if a bacterial infection isn’t responding to antibiotic treatment, targeting the sidekick bacteria might help take the primary pathogen down.